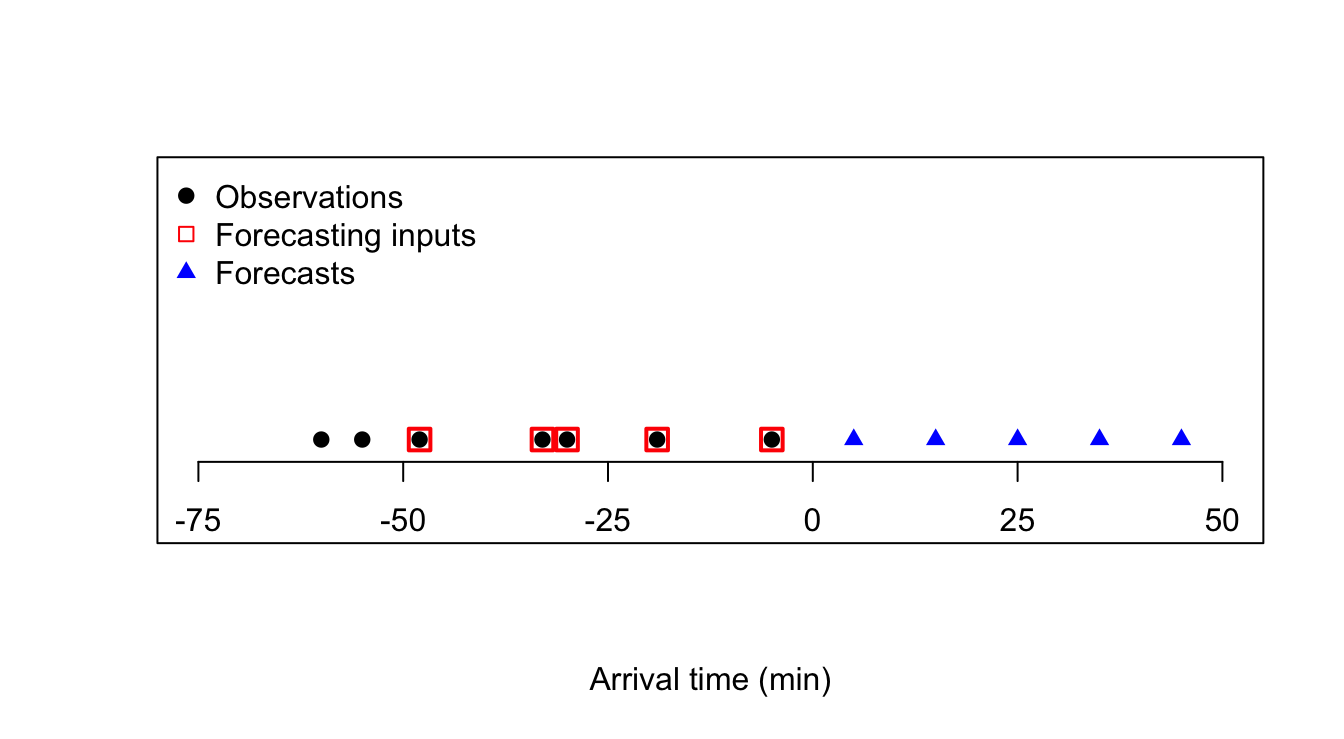

y <- c(-60,-55,-48,-33,-30,-19,-5)

yhat <- c(5,15,25,35,45)

plot(y,rep(0,7),xlim=c(-75,50),pch=19,type='p',xlab='Arrival time (min)',ylab=NA,yaxt='n',xaxt='n',ylim=c(-1,3))

axis(side=1,at=seq(-75,50,25),labels=TRUE,pos=-0.25)

points(y[3:7],rep(0,5),pch=0,cex=1.5,col='#ff0000',lwd=2)

points(yhat,rep(0,5),pch=17,col='#0000ff')

legend(x='topleft',legend=c('Observations','Forecasting inputs','Forecasts'),bty='n',pch=c(19,0,17),col=c('#000000','#ff0000','#0000ff'))

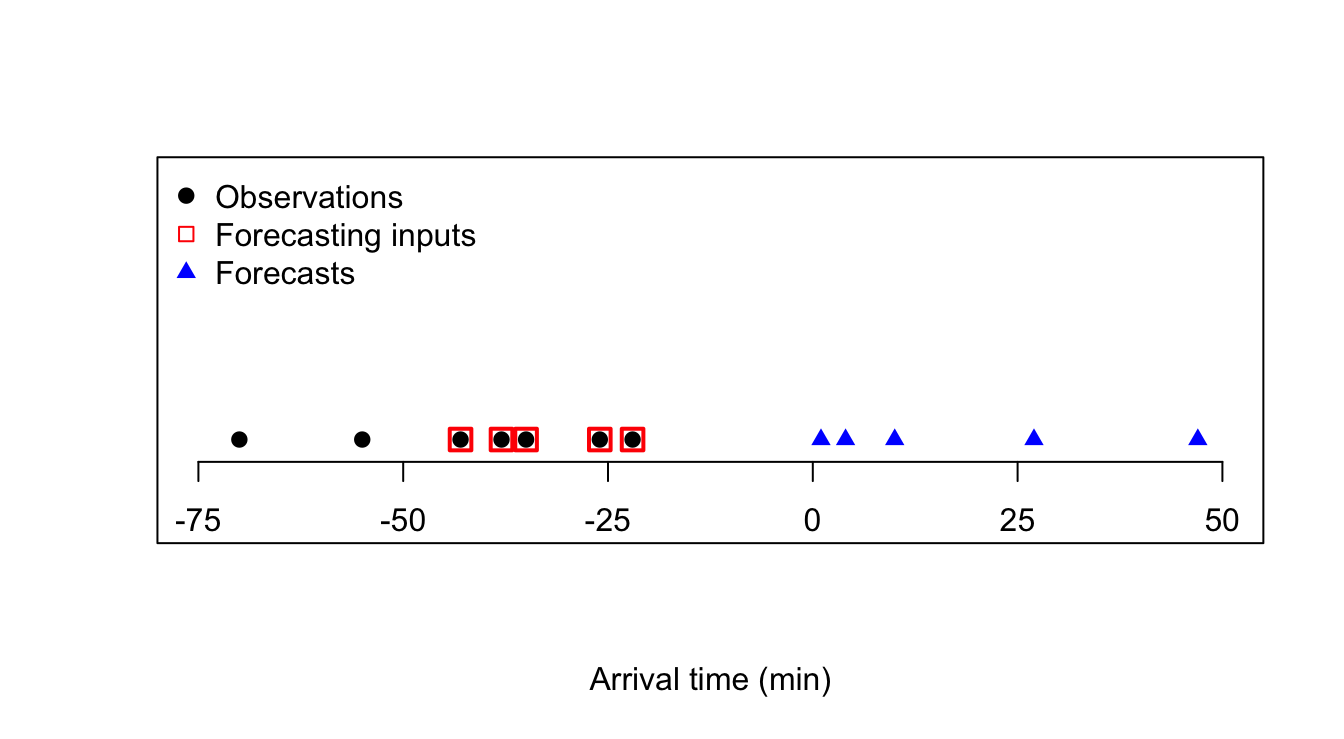

y <- c(-70,-55,-43,-38,-35,-26,-22)

yhat <- c(1,4,10,27,47)

plot(y,rep(0,7),xlim=c(-75,50),pch=19,type='p',xlab='Arrival time (min)',ylab=NA,yaxt='n',xaxt='n',ylim=c(-1,3))

axis(side=1,at=seq(-75,50,25),labels=TRUE,pos=-0.25)

points(y[3:7],rep(0,5),pch=0,cex=1.5,col='#ff0000',lwd=2)

points(yhat,rep(0,5),pch=17,col='#0000ff')

legend(x='topleft',legend=c('Observations','Forecasting inputs','Forecasts'),bty='n',pch=c(19,0,17),col=c('#000000','#ff0000','#0000ff'))